Keep Me In Your Heart: The Last Songs of 30 Legendary Artists

Endings are difficult. Whether you’re expecting a slow fade to black or you get startled by an abrupt cut, finality can be hard to accept. It's no different in rock ’n’ roll. Each song in the list below is an ending, as we remember the last songs of 30 legendary artists.

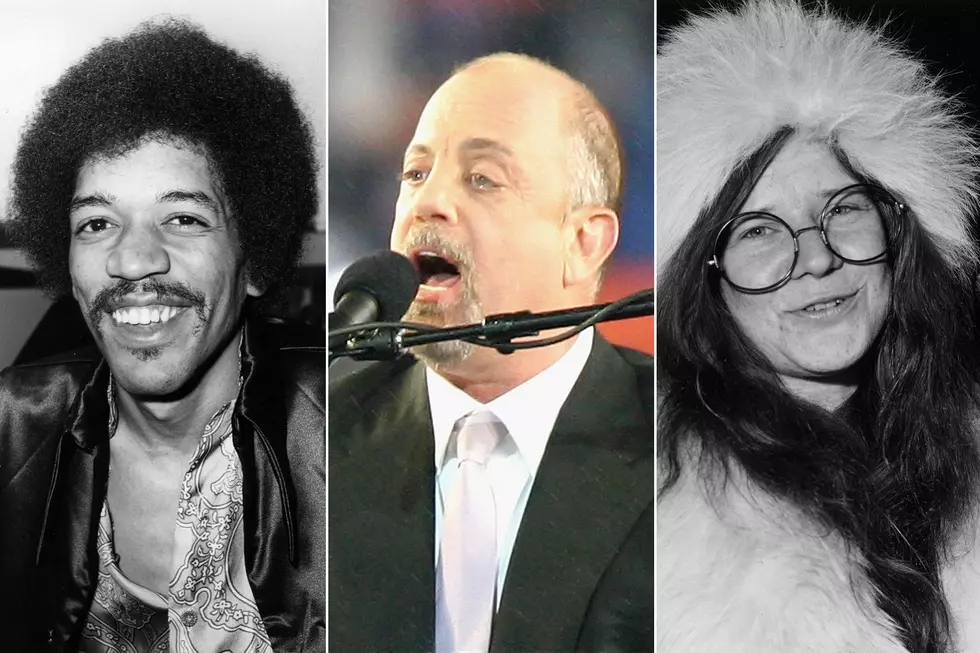

“That’s it!” Janis Joplin laughed, and it was. “I ain’t too old to die,” Bon Scott sang, and he wasn’t. Rock history is littered with musicians who died young and many of the last recordings on this list preceded a death, from Jimi Hendrix’s “Belly Button Window” to Led Zeppelin’s “I’m Gonna Crawl.” Some artists’ final studio work was done in the service of a friend (Tom Petty, Lou Reed) while others were collaborations (Lemmy Kilmister, Chris Cornell).

Of course, some of these songs aren’t the result of a rock star’s death at all. When bands break up – from the Beatles to Cream to the Police – there has to be one, last recording. And then there are musicians, such as Billy Joel, who attempt to retire from the studio, even as they continue to perform.

Some of these last hurrahs rank with the artist’s best-known material (the Doors and Roxy Music went out with classics) and others are covers: The Band and Jerry Garcia said goodbye with tributes. Some acts delivered definitive final statements about their group (Pink Floyd) or even life itself (Warren Zevon), while others provided resonant insight into their last year of life on the planet (Freddie Mercury, Kurt Cobain).

Whether laced with deep meaning or dashed off with no idea of the tragedy around the corner, here are the last songs of 30 legendary artists.

“Belly Button Window,” Jimi Hendrix

The last studio recording that Jimi Hendrix made before his death was a song about being born. Actually, Hendrix wrote the country blues tune about the months leading up to birth, imagining what it would be like for a growing fetus to observe his parents from the vantage point of a “Belly Button Window.”

Impending fatherhood for Hendrix's bandmate Mitch Mitchell was reportedly the catalyst for the composition. But Hendrix appeared to draw on his own unhappy memories of childhood for the lyrics, which suggest two parents who are less-than-thrilled with the pregnancy: “I swear I see nothing but a lot of frowns / And I’m wondering if they want me around.”

Hendrix wrote the lyrics before the melody, and the words were first attempted with the tune that would become “Midnight Lightning” in July 1970 at Hendrix's brand-new Electric Lady studios. On August 22, Hendrix recorded the final, bluesy version as a solo piece, overdubbing a wah-wah. The same day, he spent time considering what new recordings would comprise his next album – one that he would not live to see released.

Days after the session, Hendrix, Mitchell and Billy Cox were off to play the 1970 Isle of Wight festival in the U.K., followed by more European tour dates in September. Hendrix was gone less than a month after laying down “Belly Button Window,” killed by drug-related asphyxiation at the age of 27. Hendrix’s final recording later became the closing track on his first posthumous LP, Cry of Love.

“I’m Gonna Crawl,” Led Zeppelin

By most accounts, Led Zeppelin’s last recording sessions – for the In Through the Out Door album – were significantly less than harmonious. But it had more to do with some members’ rock-star lifestyles than the music.

Robert Plant and John Paul Jones, the (relatively) clean-living members of the band, led the way on the bulk of the LP’s tracks. They recorded their contributions during daytime hours at ABBA’s Polar Studios in Stockholm, Sweden. At night, Jimmy Page (in the throes of heroin addiction) and John Bonham (increasingly reliant on alcohol, the substance that lead to his demise) showed up to record their parts.

“I’m Gonna Crawl” was typical of the sessions, as the song was largely a Jones composition, created via his Yamaha GX-1 synthesizer and styled after Wilson Pickett’s “It’s Too Late.” Not only was the soul-influenced tune the last track on the album, it was the final Led Zeppelin song recorded in the studio. Under its working title, “Every Little Bit of My Love” (or “Blurt,” “Blot” or “I Could Crawl”), the song was put to tape on Nov. 23, 1978. Only piecemeal overdubs and final mixing remained after that.

When In Through the Out Door was released in August 1979, there was little suspicion that it would be Zeppelin’s final, proper studio album. The band didn't call it quits until another year or so, after a heavily inebriated Bonham died after vomiting while asleep on Sept. 25, 1980. Following his accidental death at age 32, the remaining members issued a statement: “We wish it to be known that the loss of our dear friend, and the deep sense of undivided harmony felt by ourselves and our manager, have led us to decide that we could not continue as we were.”

Although 1982’s Coda introduced “new” material in the form of leftover tracks, “I’m Gonna Crawl” remained the last song that the four members of Led Zeppelin ever created in a recording studio.

“Because,” the Beatles

Putting your finger on the Fab Four’s final recorded song isn’t a simple task. There is more than one correct answer, depending on your point of view.

You could say that “Real Love” was the last song the Beatles made in the studio, when Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr added new music to an old John Lennon tape for the Anthology project in February 1995. But John had already done his part before his death in 1980.

Or you could justify listing “I Me Mine” was the final track the Beatles made in the studio, since it was recorded for Let it Be on January 3, 1970. But Lennon wasn’t a part of that session either, having quietly departed the Beatles a few months earlier. (The song’s three-part harmonies were provided by Harrison, McCartney and Starr.)

You might be able to claim “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” was the last Beatles studio creation, because the song was finalized on August 20, 1969, the last time all four Beatles were in the studio together. But they didn’t actually record the Abbey Road epic that day, but merely supervised the editing of the track – stitching together two different versions from previous sessions and ending the song with an abrupt cut on Lennon’s request.

So the best candidate for “last Beatles song” is “Because.” Although other Abbey Road (and Let it Be) tracks would subsequently receive overdubs and edits (though never from all four Beatles working together), “Because” was the final song that the Beatles recorded as a foursome. They created the vast majority of the track – including guitar, harpsichord, bass and vocals – at Abbey Road Studios on Aug. 1, 1969.

“Having done the backing track, John, Paul and George sang the harmony,” producer George Martin recalled in The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. “Then we overlaid it twice more, making nine-part harmony altogether, three voices recorded three times. I was literally telling them what notes to sing.”

Now, hardcore Beatles fans might notice that Ringo can’t be heard on Lennon’s percussion-less song, which features the other three members singing and playing, along with Martin on harpsichord. However, to keep Lennon’s guitar and Martin’s harpsichord in lockstep, the Beatles’ steady drummer played a high-hat cymbal into their headphones as they recorded. His metronome-like playing wasn’t intended to appear on the finished version of the track.

So, even though you can’t hear Starr among the haunting vocals and austere instrumentation, he still made a significant contribution to “Because,” making it the last song that all four Beatles recorded in the studio.

“Walking on Thin Ice,” John Lennon

Lennon's final recorded work was not on one of his own tunes. His last sessions were spent working in collaboration with his wife Yoko Ono on her new-wavey single, “Walking on Thin Ice.”

Double Fantasy had just become a big collaborative hit for Ono and Lennon, who had been on a sabbatical from pop music since the mid-’70s, and they were determined to complete the leftover tracks for new singles and another LP. Elation filled New York’s Hit Factory as they gathered for work with producer Jack Douglas. Lennon even took out his old 1958 Rickenbacker 325 (the black-and-white instrument he so often had been seen clutching in the heyday of Beatlemania) to add guitar parts to the dance-pop tune – and also some keyboards – on Dec. 4.

Four days later, Lennon, Ono and Douglas added the last touches to “Walking on Thin Ice,” then listened back to what they had made. According to Douglas, all three felt they'd just finished be Ono’s first big pop smash.

“We were really celebrating, the three of us,” Douglas later told Rolling Stone. “We were celebrating the Soho News article about Yoko [an interview wittily headlined “Yoko Only”], and the new tune, and the press that Yoko had been receiving: We were really happy about that. Everything was going right at that point. On Monday evening, it seemed like everything was in gear and just perfect.”

Sadly, the night took a horrible turn as Lennon and Ono returned home to their New York residence and the former Beatle was gunned down by Mark David Chapman. John was holding the final mix of “Walking on Thin Ice” when he was shot and killed. He was 40.

The song, which found Ono ruminating on the unpredictability of life, was released about a month later on Jan. 6, 1981. “Walking on Thin Ice” carried a simple tribute under the song title on the sleeve of the single: “For John.”

“Horse to the Water,” George Harrison

George Harrison succumbed to has battle with cancer on Nov. 29, 2001 at age 58, but not before completing one last recording about two months before he died.

He traveled to Switzerland to record a song he had penned with his son Dhani Harrison titled “Horse to the Water,” backed by Jools Holland and his Rhythm & Blues Orchestra. Harrison wasn't best buddies with Holland, a pianist, TV presenter and one-time member of Squeeze. In fact, they had been connected through mutual friends. One of Harrison’s oldest pals was the British musician Joe Brown, whose daughter Sam Brown had recently been singing with Holland’s R&B Orchestra.

When Holland was planning the all-star project Small World, Big Band (also featuring Steve Winwood, David Gilmour and Sting, among others), word made its way to Harrison, who decided he had the perfect song for the album – a bluesy number about the futility of getting humans to change. When the horn-blurting track was recorded on Oct. 2, 2001, the cancer had weakened George to the point that he couldn’t play guitar on the tune. But he was able to lay down a strong, if wearied, vocal on the song he had written with his son.

“Horse to Water” came out in December of 2001, just a handful of days after Harrison died. In a sly bit of dark humor, George listed the song’s publisher as “R.I.P. Limited, 2001” instead of his usual “Harrisongs.”

A big tribute came the following year, when Holland’s Rhythm & Blues Orchestra appeared at the Concert for George on the one year anniversary of Harrison’s passing. They played Harrison’s last recorded song, with Dhani Harrison on acoustic guitar from Dhani Harrison and Sam Brown on lead vocals, paying homage to a man who was both a music legend and her dad’s departed friend.

“Badge,” Cream

Eric Clapton, another of Harrison’s friends, served as the bandleader at the Concert for George. Their friendship and occasional musical collaborations extended back to a time when Harrison was a Beatle and Clapton was in the power trio Cream.

In 1968, both bands were fraying at the edges. In fact, to help smooth the tension during sessions for the Beatles’ “White Album,” Harrison brought in Clapton as a guest, knowing that the others would be on their best behavior with an outsider present. (He also got a killer guitar solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”)

The Beatles soldiered through another year of recording and a few more albums, but Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker and Clapton decided that ’68 would see the last Cream tour and studio recordings. As a parting shot, the band put out one last LP (titled Goodbye, just to ensure there was little confusion about the situation) featuring live material and one new studio recording penned by each member. For his contribution, Clapton got a major assist from his friend.

“I helped Eric write ‘Badge’ you know,” Harrison said later. “We were working across from each other and I was writing the lyrics down and we came to the middle part so I wrote ‘Bridge.’ Eric read it upside down and cracked up laughing – ‘What's BADGE?’ he said. After that, Ringo walked in drunk and gave us that line about the swans living in the park.”

Starr didn’t receive official credit for his assistance with Cream’s, ahem, swan song, and neither did Harrison on initial copies of Goodbye and the “Badge” single – a mistake that was later corrected. Cream’s last album listed Harrison by the alias “L’Angelo Misterioso” for contractual reasons.

Harrison joined Bruce, Baker and Clapton in Los Angeles’ Wally Heider Studios to lay down the basic track for "Badge." The sessions, held during Cream's American tour dates in the fall of 1968, were overseen by producer Felix Pappalardi, who also played keyboards on the tune. A month or so later, "Badge" was completed with the addition of overdubs back in London. The glimmering, nonsensical song became Cream’s last charting song in North America, Europe and Australia. Not a bad way to go out.

“Christmas in Fallujah,” Billy Joel

After 1993’s River of Dreams, Billy Joel quit making new albums. He wasn’t done performing or touring, but in terms of creating new music (and the never-ending cycle of recording, releasing and promoting), the Joel was pretty much finished.

Pretty much, but not completely. Since 1993, each time Joel has dipped his toe in the waters of new tunes, it has been an event for his fans. In 2001, he released a collection of original classical compositions, although he did not play or produce the recording. In 2006, Joel recorded “All My Life” in tribute to then-wife Katie Lee, and Columbia Records was only too thrilled to release Joel’s first pop song in more than a decade in time for Valentine’s Day 2007.

But later that same year, Joel sought to record a new song, this time with the intent of releasing it to the public. Dismayed by the amount of time the U.S. Armed Forces had spent in Iraq and disturbed by the “sense of alienation” he sensed in letters from soldiers stationed in the Middle East, one of pop music’s most successful songwriters was spurred to action. He wrote “Christmas in Fallujah” in September of 2007.

“I was at home in Long Island and I knew as soon as I wrote it that I wasn’t the person to sing it,” Joel told Rolling Stone. “Not that I’m trying to distance myself from what I wrote, but I didn’t think my voice was the right voice. I thought it should be somebody around the age of the people who were serving over there.”

Joel enlisted Cass Dillon, a younger artist, to sing on the grinding recording, produced in the fall of ’07 and released as a digital single on Dec. 4. The proceeds were donated to Homes for Our Troops, a charity that builds houses for veterans injured in America’s 21st century wars. About a year later, Joel snarled his own lyrics for a live version of “Christmas in Fallujah,” recorded in Australia and released as a separate single dedicated to the Australian and American troops serving overseas. While some fans were overjoyed at the prospect of new material from Joel, others were surprised that an artist who had kept his work apolitical was weighing in on current events.

“People can take it anyway they want,” Joel said at the time. “I don’t get up on a soapbox and do political messages. I believe in talking about the human being, and the conditions humans find themselves in. ... I believe if an artist feels strongly about something, it should be reflected in their art.” To date, Joel hasn’t again felt strongly enough to record and release any new songs, making this collaboration his last known studio work – for now.

“Riders on the Storm,” the Doors (with Jim Morrison)

After Jim Morrison died on July 3, 1971, the Doors released three more studio albums – two without their brooding frontman (Other Voices and Full Circle) and one that employed poetry, spoken snippets and live performances that Morrison recorded before his death (An American Prayer). But for most people (even Ray Manzarek, who put a great amount of energy into kinda, sorta resurrecting his former band in the ’90s and ’00s), the Doors ended once Morrison was gone.

From that perspective, “Riders on the Storm” is the band’s final studio recording. Made in December 1970, it features the last work that Manzarek, Robby Krieger and John Densmore did for the L.A. Woman LP and Morrison’s final vocal with the Doors.

“Robby and Jim were playing, jamming something out of ‘Ghost Riders in the Sky,’” Manzarek told Uncut in 2011. “I proposed the bass line and piano part; the jazzy style was my idea. Jim already had the story about a killer hitchhiker on the road.”

The Doors’ mysterious epic wasn’t merely about a spree killer (although Morrison had mentioned hitchhiking murderer Billy Cook in an interview), but also dealt with love and loyalty. Morrison wallowed in the darkness to deliver his vocal, but his bandmates claimed he was more focused than he had been in years for the five-day L.A. Woman sessions, which came at the end of a rough year that included his infamous arrest for indecent exposure. Co-producer Bruce Botnick remembers that it was Morrison who voiced a desire to make “Riders on the Storm” even more cinematic.

“We all thought of the idea for the sound effects and Jim was the one who first said it out loud: ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to add rain and thunder?’,” Botnick said in 2011. “I used the Elektra sound effects recordings and, as we were mixing, I just pressed the button. Serendipity worked so that all the thunder came in at all the right places. It took you somewhere. It was like a mini movie in our heads.”

Then Densmore had the idea for Morrison to record a second, whispered vocal on top of the traditionally sung one. It was both a different way of adding echo to Morrison's voice and another spooky addition to the recording. That whispered take on the lyrics was the last thing he did with the Doors.

“How prophetic is that? A whisper fading away into eternity, where he is now,” Manzarek later ruminated. “Viewing it from the outside, you can put a neat little bow on it and see it as our last performance, but for us we were just playing our butts off. Fast, hard and rocking, but cool and dark, too.”

“Riders on the Storm” was also the final Doors single to be released during Morrison’s lifetime. It became a Billboard hit the same week in 1971 that he was found dead in a Paris apartment at age 27.

“Blue Yodel #9,” Jerry Garcia

By 1995, a lifetime of health problems and drug abuse had taken a toll on Garcia. The Grateful Dead legend was no longer so confident in his playing abilities or as keen to perform – although Garcia still agreed to participate in a Jimmie Rodgers tribute album being curated by his friend Bob Dylan.

Like Dylan, Garcia counted the “Singing Brakeman” among his influences and had covered “Blue Yodel #9 (Standing on the Corner)” in the ’80s with the Jerry Garcia Band. So when Dylan came calling, Garcia knew exactly what song he would contribute to the collection. He just didn’t know that it would end up being his final studio recording.

Garcia didn’t record the Rodgers classic with the Dead, but some other long-time musical pals, including mandolinist David Grisman and bassist John Kahn. “It was a last-minute kind of thing,” Grisman told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1997.

In late July of 1995, Garcia called Grisman, wondering if he could arrange a recording at the mandolin player’s home studio. Garcia wanted to do the session the following day, but Grisman had other commitments that caused the session to be pushed back. They eventually got together on the following Sunday, the day before Garcia checked himself into the Betty Ford Clinic in one of many attempts to get clean.

Nobody gathered at Grisman’s studio, including drummer George Marsh and dobro player Sally Van Meter, had any advance notion that they would be recording the Rodgers tune. Luckily, Grisman owned a copy of “Blue Yodel #9” and was able to transcribe the lyrics for his buddy. “This is the way we usually did things, actually,” Grisman admitted.

The quintet did five bluegrassy renditions of the song, felt they got it right and parted ways. Garcia was off to rehab the following morning, although he didn’t mention this plan to his collaborators. He died of a heart attack within weeks, suffered on Aug. 9, 1995 while at a different rehabilitation clinic. Garcia had just turned 53.

Grisman now had possession of this final recording, and he did his best to do right by history and finish the track (adding a prelude with Kahn and overdubbing horns) before turning it over to Dylan’s people for Songs of Jimmie Rodgers: A Tribute. The album, with Garcia’s last studio work, came out in August 1997.

The cover of “Blue Yodel #9” also featured some of last studio work by Kahn, who died in 1996 from a heart attack. Reflecting on the Sunday morning recording session a couple of years later, Grisman might have sensed the end was near: “Neither one of them looked real great that day.”

“You Know You’re Right,” Nirvana

The members of Nirvana didn’t expect to get much out of the sessions that resulted in the band’s final recorded song. They didn’t book a significant amount of studio time. They weren’t planning on making a new album. It was just a weekend of sessions in Seattle between legs of their 1993-94 tour.

“That session was kind of fly-by-night,” Dave Grohl recalled in 2004. “I remember being on tour and Kurt [Cobain] talking about wanting to go into a studio and record some stuff.”

Grohl, Cobain and Krist Novoselic originally thought they might land at Seattle’s Studio X before Grohl suggested checking out a studio that was a couple of blocks from where he lived. Robert Lang Studios in North Seattle turned out to be this huge underground facility that had 24-foot-high ceilings carved out of a hillside. The band booked “Bob’s Bunker,” as Novoselic nicknamed the place, for Jan. 28-30, 1994.

Cobain was a no-show for the first two days, so Grohl and Novoselic goofed around on instrumental stuff and played some of their own material – including renditions of future Foo Fighters tracks “Big Me” and “February Stars.” Cobain finally appeared on the 30th. After listening to some of the previous days’ results, and giving the studio’s sound his approval, he set to work with his bandmates.

“Kurt came in the last day and we were like, ‘OK, what do you wanna do?’,” Grohl told Studio Brussel in 2014. “And Kurt said, ‘Well, why don’t we do that song we’ve been doing at soundcheck?’ And so we rehearsed it, I think, once, and then recorded it.”

The untitled song was given the studio moniker “Kurt’s Tune #1” at the time. It was something that had come together over the course of the fall tour to promote In Utero. The abrasive, dynamic song had only made one appearance in an official set, during an October show in Chicago. “We bombed it together fast,” Novoselic recalled in Heavier than Heaven. “Kurt had the riff, and brought it in, and we put it down. We Nirvana-ized it.”

The recording came together quickly, although it was not a one-take wonder, as some later suggested. Looking for an interesting introduction to the song after a couple of takes, Cobain came up with the distinctive chiming sound that opens and closes the final recording by plucking the taut strings above the nut (or below the bridge) on his Univox guitar. Later that day, Cobain recorded the lyrics to the song that would become known as “You Know You’re Right.”

Aside from a jam session, that was it. Nirvana packed up, Novoselic took possession of the weekend’s tapes and the band headed to Europe that week for a run of live shows that turned out to be Nirvana’s last. Cobain was found dead on April 8, 1994. He was 27.

“You Know You’re Right” collected dust at Novoselic’s house for a few years before he and Grohl had the idea of releasing Nirvana’s final studio recording as part of a box set. They were initially blocked, however, by Cobain’s widow Courtney Love. In time, they eventually agreed to put out the song as the lead single from a Nirvana greatest hits album, simply titled Nirvana and released in October 2002. Nearly nine years after it was recorded, “You Know You’re Right” showcased the band’s enduring relevance, as the single became a radio, chart and video success and helped the compilation go multi-platinum around the world.

“On the Way Home,” Buffalo Springfield

By the time Buffalo Springfield released their third album, Last Time Around, on July 30, 1968, the band wasn’t even a band anymore. They had been existing on borrowed time since at least the previous year, mostly due to issues with Neil Young and Bruce Palmer. The former had a tenuous commitment to playing and recording with the band (he was replaced by David Crosby for a performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival) while the latter had a knack for getting arrested for drug possession.

As his arrests piled up, Palmer was deported back to his native Canada in 1967 and temporarily replaced in Buffalo Springfield – until he snuck his way back down into California later in the year. Young came back to the group with Palmer’s return. Even though the group wasn’t destined to hold together for long, they kept playing and recording.

The final recording featuringh all five original members (Young, Palmer, Stephen Stills, Richie Furay and Dewey Martin) was the mid-tempo, R&B-inflected “On the Way Home,” a tune written by Young and recorded by Buffalo Springfield between mid-November and mid-December 1967 at Sunset Sound studios in Los Angeles.

Not long after that, Palmer had another drug arrest and was again deported from the States. This time, he was permanently replaced on bass by Jim Messina, who was also producing Buffalo Springfield’s next LP. Still, that was like using Elmer’s glue to prevent continental drift. Young again lost interest and Last Time Around was mostly cobbled together by Furay and Messina from various sessions spanning 1967-68. Not one member of the band appears on all 12 of the album’s tracks, with Young on only half, Martin on fewer than that and Palmer only playing on one. After a gig in May 1968 at the Long Beach Arena, Buffalo Springfield was done.

“On the Way Home” became the band’s final single – a modest hit in the summer of ’68, though nothing close to “For What It’s Worth – and Buffalo Springfield splintered into projects that would have sustained success. Furay and Messina formed the country-rock band Poco, Stills became part of Crosby, Stills and Nash (sometimes including Young) and Young began his solo career.

“Mercedes Benz,” Janis Joplin

“That’s it!” Janis Joplin announced, followed by a cackle, at the end of “Mercedes Benz.” These would be the final moments recorded by one of music’s most beloved singers, on a song that so nonchalantly displayed her infectious sense of humor and remarkable talent.

Joplin came up with the silly tune a couple of months before she recorded it in August 1970, between shows in Port Chester, New York. During a drinking session with musician pal Bob Neuwirth and actors Rip Torn and Geraldine Page, Janis kept singing the first line of a song by poet Michael McClure: “Come on, God, and buy me a Mercedes-Benz.” More rounds of drinks helped her extrapolate the solitary verse into a longer composition, with Joplin humorously asking her maker for a color TV and “a night on the town.” Neuwirth assisted and wrote the lyrics down on a bar napkin.

“We were all sitting around banging beer mugs on the table and chanting what existed of the song, which was the first couple of lines – and we finished it at this bar,” Neuwirth recalled to Yahoo! Music in 2013. Soon after, Joplin got word that she needed to be on stage for her second performance, during which she “started singing this song – by herself, a cappella.”

Janis performed “Mercedes Benz” a couple of times on tour before she went to Los Angeles’s Sunset Sound studios in September to record her next album, which would become the posthumous release, Pearl. The singer didn’t necessarily have designs on recording her minute-and-a-half, anti-consumerist goof of a song, but when the more complicated multi-track equipment broke down on Oct. 1, she filled time by recording “Mercedes Benz.” She sang it alone and a cappella – just like in concert – on the studio’s backup, two-track recorder.

“It’s just the pure power of her charisma that causes it to be notable,” Neuwirth said. “The little cackle at the end, it’s so Janis – and that was more indicative of the woman than anything that’s been written about her. I mean, she was a funny girl.”

Sadly, that laugh would be the last recorded work ever heard from Joplin. Three days later, on Oct. 4, 1970, she was found dead from a heroin overdose at the age of 27. With the sessions for Pearl incomplete, “Mercedes Benz” was pressed into service on the LP’s tracklist, simply because there weren’t other options. The a cappella tune was released on the album in January 1971 and as the b-side to the single “Cry Baby” the same year – and it eventually outpaced the a-side to become one of Joplin’s best-known songs. “That’s it!”

“Mother Love,” Freddie Mercury (with Queen)

Freddie Mercury's health was badly faltering after the end of work on Innuendo, released February 1991. Suffering from the effects of AIDS, the once-dynamic frontman was becoming more tired and weak. Mercury knew he wouldn’t live long enough to complete the band’s next LP – but he could help his bandmates begin.

“We had had the discussions and we knew that we were totally on borrowed time because Freddie had been told that he would not make it to that point,” Brian May said in the documentary Queen: Champions of the World. “I think our plan was to go in there whenever Freddie felt well enough, just to make as much use of him as much as possible; we basically lived in the studio for a while and when he would call and say, ‘I can come in for a few hours,’ our plan was to just make as much use of him as we could. You know he told us, ‘Get me to sing anything, write me anything and I will sing it and I will leave you as much as I possibly can.’”

One of those things was “Mother Love,” the last song co-written by Mercury and May and the last vocal that the singer ever recorded. The lyrics give an idea of the pain and sadness Freddie was feeling (and that May was witnessing) during the singer’s last year alive. He cries about “comfort and care,” begs for love and pleads, “I long for peace before I die.”

Mercury recorded these words in mid-May of 1991 at Queen’s recording base of Mountain Studios in Montreux, Switzerland. But he left the song unfinished because he just couldn’t push his body any further. Mercury was only six months away from dying.

“After he’d finished the second verse, he said, ‘Oh I don’t feel too well. I’m going to go home and we'll finish it tomorrow’ – and he never did,” May said in Days of Our Lives. “That was the last time I saw Freddie in the studio.”

Mercury’s died on Nov. 24, 1991 at the age of 45. About two years later, the remaining members of Queen – May, John Deacon and Roger Taylor – regrouped to finish those final recordings, as well as some material from earlier sessions. May sang the final verse of “Mother Love” in Mercury’s absence. This was followed by the sound of a sing-along from Queen’s famous 1986 show at Wembley Stadium, hyperspeed snippets of every one of the band’s songs and a 1972 sample of Freddie singing, “I think I’m going back to the things I learnt so well in my youth.” A baby’s cry completed the circle of life that the members of Queen meant to convey in tribute to their fallen friend.

“Mother Love” was released on Made in Heaven, Queen’s 15th and final studio album, in November 1995, just less than four years after Mercury’s death.

“Jacksonville Kid,” Ronnie Van Zant (with Lynyrd Skynyrd)

Lynyrd Skynyrd frontman Ronnie Van Zant grew up with country music on the radio. As he got older, he increasingly gravitated to the country stars who branded themselves outlaws, artists such as Waylon Jennings and, especially, Merle Haggard. The latter remained Van Zant’s go-to musician on the tour bus, well into Skynyrd’s successful mid-’70s run.

“Ronnie’s favorite guy was Merle Haggard, and he just listened to that every day,” Skynyrd guitarist Gary Rossington told CMT in 2009. “I loved it. Billy [Powell, keyboardist] used to fight with him. He liked Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer – and keyboard stuff. But we listened to the good old stuff.”

So, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s first studio-recorded Haggard cover was a long time coming. When Van Zant and his bandmates selected “Honky Tonk Night Time Man” for the Street Survivors sessions in 1977, it was hardly an unexpected move for a band that blended the twang and storytelling of country music with the aural assault of rock ’n’ roll.

Although the band’s version of Haggard’s 1974 song appeared on the final album from Lynyrd Skynyrd’s original run), Van Zant also toyed with a virtual songwriting collaboration with his country hero. Using Haggard's “Honky Tonk” melody, Van Zant wrote new autobiographical lyrics to the tune centering on his hometown. He called the song “Jacksonville Kid.”

In what is believed to be Van Zant’s final studio vocal, he sang about loving his city, despite feeling out of place amongst its disco scene or even outright unwanted by some of the residents. “Lord, I’m on their wanted posters,” Van Zant sang, eager to embody Haggard’s outlaw image. “I can’t show my face in town.” The song lost out to Lynyrd Skynyrd's take on the Haggard original for the final cut of Street Survivors, and “Jacksonville Kid” wasn’t officially released until 2000.

Only a few months after he recorded the tune in August 1977, Van Zant was one of six people killed when Lynyrd Skynyrd’s tour plane ran out of fuel between stops and crashed in Mississippi on Oct. 20, just days after the release of the band’s new album. Van Zant was 29. At his funeral in Florida, Van Zant's family had Merle Haggard’s “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am” played for the sad occasion. The Jacksonville Kid was a Haggard fan to the end.

“Given All I Can See”/“Here She Comes Again,” Tom Petty (with Chris Hillman)

When Tom Petty died at the age of 66 on Oct. 2, 2017, the last major studio project he had worked on was neither a new Heartbreakers record nor a solo offering. It was the latest album by former Byrds member Chris Hillman. Bidin’ My Time was recorded in 2017 and released shortly before Petty’s death from mixed drug toxicity.

Hillman, who was also in the Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas and the Desert Rose Band, credited Petty (along with long-running friend Herb Pedersen) for convincing him to make his first studio album since 2005. Petty agreed to produce Bidin’ My Time at his own studio.

“I didn't think I would ever make another record,” Hillman told Billboard before the album was released. “This just came along through Herb and Tom Petty. ... After I had a long conversation with Tom in the fall, November, I said, ‘Are you sure you want to do this?,’ and he was, ‘Do you want me to?’ … He said, ‘Great, we’ll use my old studio and everything.’ … All in all it was a joy. I’ve never had as much fun recording.”

Not only did Petty produce the sessions, he couldn’t help but join in a little bit, playing harmonica on “Given All I Can See” (which Hillman called his favorite tune on the disc) and contributing electric guitar on “Here She Comes Again” (a song Hillman had written with former Byrds bandmate Roger McGuinn but never properly recorded).

These two songs are thought to be Petty’s final studio recordings. Although neither were made with the full Heartbreakers band, Tom did enlist his group’s help for the Hillman project. For instance, Benmont Tench played organ on “Here She Comes Again,” Steve Ferrone drummed on both tracks that feature Petty and guitarist Mike Campbell showed up elsewhere. In addition, Hillman covered Petty’s “Wildflowers” on the album.

That seemed like a nod to the praise and support Petty gave the Byrds throughout his career, from producing records by former members to covering Byrds chestnuts such as “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” and “So You Wanna Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star” with the Heartbreakers. After Petty died, Hillman expressed his eternal gratitude for Petty’s music, collaboration and friendship. “I loved Tom so much. He was such a blessing in my life,” Hillman said. “Tom touched everyone with his beautiful music.”

“Little Martha,” Duane Allman (with the Allman Brothers Band)

This gentle tangle of acoustic guitars was the first song Duane Allman wrote by himself for the Allman Brothers Band. “Little Martha” also was the last tune he ever recorded in a studio.

In the fall of 1971, the Allmans were busy, after recording a couple of studio albums and slowly making a name for themselves on the touring circuit, the group had finally broken big with the legendary live album At Fillmore East. In between dates on a congested tour schedule, the Allman Brothers attempted to record stuff for a follow-up album any time they had a few days off from the road.

A break in October gave Duane, Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Berry Oakley, Jai Johanny Johanson and Butch Trucks an opportunity to head down to Miami’s Criteria Studios to record with producer Tom Dowd. There, the Allmans made their last recordings with Duane (all to be featured on Side Three of 1972’s Eat a Peach): “Stand Back,” “Blue Sky” and “Little Martha.”

Duane claimed that the melody of the last one came to him in a dream. Shortly after Jimi Hendrix had died in 1970, Allman's subconscious placed the two guitar greats in a Holiday Inn bathroom. Allman remembered that Hendrix walked him over to a sink that had special musical abilities.

“Jimi bent down toward the silver faucet, turned it gently, and kept teasing and turning, and as he did, a beautiful guitar riff came floating out,” Galadrielle Allman said, discussing her dad’s dream in Please Be With Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman. “The melody Jimi gave him was the seed of ‘Little Martha’.”

The tune was a dream-world gift from Hendrix, but the title (and, perhaps, mood) came from something more tangible. Some have suggested that “Little Martha” refers to Martha Ellis, a 12-year-old girl buried and immortalized in a statue at Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Ga. Others are confident that “Martha” was Duane’s nickname for his lover Dixie Meadows, because of her preference for old-timey clothing, and that the song’s peaceful nature was dedicated to her.

Regardless of inspiration, “Little Martha” was put to tape by Allman, Betts and Oakley in early October of ’71. Listening to the results, the band decided that Oakley’s bass was too heavy for the song and his part was mixed out of the version on Eat a Peach.

A few weeks after the Miami sessions, on Oct. 29, Duane Allman died after a motorcycle accident in Macon. He was 24 years old. The guitarist was buried at Rose Hill, the same resting place, perhaps of “Little Martha.”

“Avalon,” Roxy Music

Inspiration for Roxy Music's final studio album included the King Arthur legend, landscapes in Ireland (where frontman Bryan Ferry began writing material for the LP) and the band members’ drug habits. All three combined for the album’s mystical, mythical aesthetic, or “spaced-out stuff,” as guitarist Phil Manzanera once described it.

Although Roxy Music had cut a version of “Avalon” during the bulk of recording at Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas, when the sessions moved to the Power Station in Manhattan (for finishing and mixing), co-producer Rhett Davies and the band discovered that the recording just wasn’t up to the standard of the remainder of the material. As the title track of the LP, there was only one thing to do.

“With the ‘Avalon’ song, we had to recut the entire song right at the end of the album,” Davies told Sound on Sound in 2003. “So, as we were mixing, we recut the entire song with a completely different groove. We finished it off the last weekend we were mixing.”

Amidst Ferry’s dreamy, Arthurian fantasies of paradise, a subtle reggae groove manifested itself – the result, Manzanera once guessed, of having recorded at the same studios as Bob Marley did back in the mid-’70s. The song developed an extra Caribbean touch with the addition of a backing vocalist.

“In the quiet studio time they used to let local bands come in to do demos,” Davies said of the Power Station. “Bryan and I popped out for a coffee, and we heard a girl singing in the studio next door. It was a Haitian band that had come in to do some demos, and Bryan and I just looked at each other and went, ‘What a fantastic voice!’ That turned out to be Yanick Etienne, who sang all the high stuff on ‘Avalon.’ She didn’t speak a word of English. Her boyfriend, who was the band’s manager, came in and translated. And then the next day we mixed it.”

With a new groove, and a new vocalist, added to the track, both Avalon and its title track were complete. Released in May 1982, Roxy Music’s platinum eighth album earned the band both commercial and critical success before they broke up in 1983. Some of Roxy’s members reunited in the 21st century and allegedly recorded new material, but it has yet to be heard by the public, leaving “Avalon” as their last official studio recording.

“Midnight Rambler,” Brian Jones (with the Rolling Stones)

The Rolling Stones might never have existed if it hadn’t been for Brian Jones. But as the band moved away from blues and R&B covers toward material from the songwriting team of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, Jones started to feel less and less integral.

It was a long, slow departure from 1967-69, marked by Jones’s dependency on drugs, a sort of love triangle between Jones, Keith Richards and Anita Pallenberg, and Jones' decreasing lack of interest in the Stones (and visa-versa). Although Jones made some significant musical contributions to the band’s releases in those years – often playing a variety of instruments – he was also sometimes unable to perform and increasingly didn’t even show up to recording sessions.

His time with the Stones ended with a whimper. Jones' final contributions to a Rolling Stones studio release came in the form of autoharp played on “You Got the Silver” and congas on “Midnight Rambler.” Both songs later appeared on Let it Bleed, making it the only Rolling Stones studio LP to feature the work of Jones and his replacement, Mick Taylor.

“You Got the Silver” was recorded in February of ’69, and “Midnight Rambler” was made in the second half of April at Olympic Sound Studios in London. While the autoharp is audible on the former, Jones’s conga contribution on the latter is not. It even has been rumored that Jones never played any such part on the multi-part blues track and that the Rolling Stones merely credited him to be nice.

But “nice” wasn’t really the tenor of the relationship between Jones and the band at that point. After all, this was the man who had foolishly left the band’s Jaguar out on the street to be towed away, was a frequent no-show for Rolling Stones commitments and had been arrested on drug charges, twice – likely snuffing any chance he had of securing a visa to tour the U.S., which they were planning to do soon.

In June 1969, the other four Stones booted Jones from the band (although he was able to save face by announcing his own departure) and replaced him with Taylor. Less than a month after he parted way with the Rolling Stones, Jones was found dead in his swimming pool at the age of 27, with evidence of drug and alcohol abuse – although the cause of his passing was infamously determined by the coroner to be “death by misadventure.”

There remains some controversy regarding the circumstances of Jones’s death, just as no one is completely certain that he recorded a conga part for “Midnight Rambler.” But it remains, officially, his last misadventure in the recording studio.

“The Wanderlust,” Lou Reed (with Metric)

Like a handful of other legends on this list, Lou Reed’s final known studio recording wasn’t for one of his own projects, but a favor for a friend. In 2010, Reed had crossed paths with Emily Haines of Canadian indie rockers Metric during the Vancouver Winter Olympics. Star-struck, Haines was surprised to find that Reed was an admirer of her music and the two became friends.

Haines performed with Reed in the following years at a couple events, which tightened their bond. So, when Metric were recording their 2012 album Synthetica at Electric Lady Studios in New York City and stumbled into trouble on “The Wanderlust,” Haines knew exactly who could improve the track.

“When I sang it, or the guys sang it, it was like, ‘what is this... Glee?’” Haines told Spinner. “This is not working, but we needed this feeling expressed of just keep on keeping on. I called Lou and he said yes.”

Reed requested that he sing the entire song with Haines, with their microphones set facing each other in the studio. That’s how they recorded it, although Metric ended up only using Reed’s vocals for the chorus on the version of “The Wanderlust” that was released on Synthetica.

“We thought it needed to be a moment, not stand out from the record,” Haines said. “At some point maybe we’ll release that version.”

The following year, on Oct. 27, 2013, Reed died from liver disease at age 71, leaving behind a rich musical legacy – and one last recording on a Metric album.

“Don't Stand So Close to Me ’86,” the Police

After their blockbuster tour to promote Synchronicity, the Police went on hiatus in 1984. Sting began his solo career, Stewart Copeland worked in film and Andy Summers made a record with Robert Fripp. Although the trio kept it quiet at the time, given the fractious relationship between members, it was possible that the Police were over.

Despite Sting’s solo success (and an instinct that told him it was time to move beyond the band that had made him a household name), he agreed to regroup with Copeland and Summers for a few shows in June 1986 to support Amnesty International. The performances were up-and-down, but went well enough that the Police found themselves back in the studio in July.

The sessions were purportedly for the trio to re-record some of their best-known material for a planned greatest hits album, although management booked extra time with the notion that the musicians would gel once again and produce some new stuff. Perhaps, they’d even begin the next Police album. But any hope of this was dashed the day before the studio time was set to begin, when drummer Copeland broke his collarbone playing polo.

“The studio was booked for three weeks,” Summers told Rolling Stone in 2007. “If Stewart hadn’t fallen from his bloody horse, we would have jammed and out of that may have come something new. Instead, we had a Synclavier and a Fairlight and a big fight over which was better.”

The Police had a history of studio fights, and these sessions only continued the trend. Because Copeland was unable to drum, the trio relied on electronic drums for a reworked version of their 1980 smash, “Don’t Stand So Close to Me.” Copeland preferred to use his Fairlight CMI sampling keyboard to program the drums, while Sting demanded that the group use the Synclavier because he liked that keyboard better.

The group acquiesced to Sting’s wishes, but when a studio engineer struggled for a couple of days to finish the drum track on the Synclavier, Copeland stepped back in and completed it on the Fairlight anyway. Copeland later called the disagreement “the straw that broke the camel’s back” as far as any group unity was concerned. “I played my guitar part on the first night,” Summers said. “The other 20 days was those two arguing about the two machines.”

There would be no new album from the Police in 1986, or ever. In fact, the band were lucky to come away with any new recordings at all. The only two songs produced at the sessions were slowed-down, extra-synthy versions of “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” and “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da.” The former, clumsily retitled “Don’t Stand So Close to Me ’86,” was released as a single and a video in October to promote the collection Every Breath You Take: The Singles. The latter, which the band apparently liked even less, was later dumped on the SACD version of a 1995 hits compilation.

Although the Police reunited in 2007 to tour, they resisted entering the studio again, leaving those often-maligned ’86 recordings as their last.

“We are the Ones,” Lemmy Kilmister (with Chris Declercq)

Chris Declercq practically won the rock fan lottery. In 2005, he moved from his native Switzerland to Los Angeles and made his way to West Hollywood’s famous Rainbow Bar and Grill on the Sunset Strip. As long as Motörhead frontman Lemmy Kilmister had been living in California, he’d been a regular at the Rainbow and Declercq was fortunate to meet one of his heroes at the bar, strike up a conversation and give him his demo.

Kilmister must have liked what he heard, because he ended up collaborating with the Swiss musician less than a decade later. The two co-wrote a song called “We are the Ones,” with lyrics by Declercq and vocals by Kilmister, then began recording the tune in 2014 at Paramount Studios. In March 2015, less than a year before his death, Kilmister laid down a bass part in a session that produced his last known solo recording.

In his later years, Kilmister experienced a slew of health problems, although his raspy vocal and thunderous bass sound positively vital on “We are the Ones.” In the months following the recording session, he tried to cut back on smoking, dealt with a lung infection and turned 70. Just two days after his birthday, Kilmister was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Two more days after that, on Dec. 28, 2015, he was dead from other issues, including congestive heart failure and prostate cancer.

About a year following Kilmister’s passing, Declercq sought to finish “We are the Ones” with producer Martin Guigui (who also played keyboards on the song) and drummer Josh Freese at Dave Grohl’s Studio 606. The song became a tribute to a hard-rock legend.

“I focused on cracking the code to the song’s truth, which is Chris’ artistic ability to craft a lyric and melody for Lemmy’s rock and roll persona, and then Lemmy’s soulful vocal delivery which is the heart of the song,” Guigui told Rolling Stone. “Ultimately, my role was to stay true to Chris’ vision, and complete perhaps what Lemmy would have envisioned as well. It is really an homage to Lemmy, with his participation, which is wild.”

Adding the finishing touches, Declercq recorded with an ace of spades attached to the headstock of his Les Paul guitar, seeking to do right by the man that had helped him get a break in the music industry. “You opened a door no one else wanted to open for me,” Declercq said in a 2017 tribute to Kilmister. “You allowed me to share precious moments with you as a composer, musician and friend. By helping me, you showed that you were the most generous, humble and honest man. I am honoring your gift every day and you are forever in my heart.”

“Keep Me in Your Heart,” Warren Zevon

After avoiding doctors for decades, Warren Zevon was diagnosed with terminal mesothelioma in the summer of 2002. Given months to live, Zevon refused treatments that might comfort him but hinder his abilities. Instead, he went to work.

“I don’t think anybody knows quite what to do when they get the diagnosis. I picked up the guitar and found myself writing this kind of farewell,” Zevon said about “Keep Me in Your Heart” in a VH1 documentary. “Instantly I realized I’d found what to do with myself. On reflection, it might be a little bit of a ‘woe is me’ song, but it made me realize what I was going to do with the rest of the time.”

With a batch of songs already written (or at least begun), Zevon quickly started recording what would be his final studio album, The Wind, in the fall of ’02. His creative partner was again Jorge Calderón, one of Zevon’s longest-running collaborators, but he got plenty of all-star assistance on the record too. The Wind featured contributions from musical pals Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Tom Petty and Eagles Don Henley, Joe Walsh and Timothy B. Schmit, among others.

While doctors warned Zevon that he could die before the end of the year, he outperformed the prognosis and worked on the album whenever his body would allow. By April 2003, when Zevon was no longer well enough to go into the studio to record, his collaborators brought the studio to him. Session great Jim Keltner and Calderón recorded their gentle parts of “Keep Me in Your Heart” in the studio and Jorge helped create an impromptu recording station in Zevon’s living room, so he could lay down his final vocal. With his pregnant daughter Ariel looking on, Zevon sang the words he had written after realizing his time on earth wouldn’t be long: “If I leave you, it doesn’t mean I love you any less / Keep me in your heart for awhile.”

Zevon lived to see The Wind completed, then released on Aug. 26, 2003, with “Keep Me in Your Heart” as the album’s final track. He died two weeks later, on Sept. 7, more than a year after he had been told he had just a few months remaining. He was 56.

“Do You Want to Rock?,” Phil Lynott (with Colbert Hamilton)

After Thin Lizzy disbanded in 1984, Phil Lynott was in trouble. The last years of his life were rough ones, as Lynott turned to drugs and alcohol to soothe his calamities, both personal and professional.

Yet Lynott kept working. In his final weeks alive, Lynott produced a session for Colbert Hamilton, a British singer who specialized in early rock ’n’ roll and called himself “Black Elvis.” Hamilton recorded a rave-up called “Do You Want to Rock?” in December 1985 at Lynott’s home studio in Richmond, England, with Lynott playing bass on the track and singing background vocals.

“He was on the ball in terms of his playing, but he was going at his own pace,” Hamilton told the BBC in 2009. “I was aware through my manager of the time that he was taking drugs and, looking back, he was in poor health.” The recording, which would be Lynott’s last turn in a studio, was pretty much forgotten in the wake of the former Thin Lizzy frontman’s death on Jan. 4, 1986, following a collapse on Christmas and a long hospital stay. After years of substance abuse, Lynott died from pneumonia and heart failure. He was 36.

“Do You Want to Rock?” gathered dust under Hamilton’s bed for the next quarter century, the track having never been given a final polish. It was uncovered in 2009 when fellow musician Paul Murphy was working on a documentary tracing Lynott’s life in both England and Ireland. Hamilton allowed it to be released as part of Murphy’s project. “The audio is a bit rough as it was very much a work in progress,” Murphy said at the time, “but Lynott’s unmistakable sound can be heard throughout.”

“You Never Knew My Mind,” Chris Cornell

The Soundgarden singer’s last known recording was a collaboration from beyond the grave – in more ways than one. Not long before Chris Cornell committed suicide on May 18, 2017 in a Detroit hotel room, the singer recorded “You Never Knew My Mind,” based on a pair of poems the late Johnny Cash had written 50 years earlier.

John Carter Cash, Johnny’s son, tapped Cornell to contribute to a project that became Johnny Cash: Forever Words, an album featuring a variety of artists putting new music to poems, lyrics and letters that the elder Cash penned before his death in 2003. Cash memorably covered Soundgarden’s “Rusty Cage” for his 1996 Unchained album, and a couple of decades later, Cornell was sort of returning the favor.

“I met [Cash] once or twice in my life, and he was so gracious and he was such an influence on me as a musician,” Cornell said at the time he recorded “You Never Knew My Mind.” “And he also covered a song that I wrote. Since that time, I’ve felt like he’s maybe one of the bigger presences in my life, in terms of artists that I’m a fan of.”

Cornell recorded his contribution at the Cash Cabin Studio in Hendersonville, Tenn., and – not long before his own passing – spoke about the “Twilight Zone” nature of this collaboration taking place in the cabin that Johnny had built. When preparing to release Forever Words in 2018, nearly a year after Cornell’s death, John Carter Cash revealed that Cornell had combined two of his father’s poems for the song.

“There were actually two pieces – there was ‘You Never Knew My Mind’ and ‘I Never Knew Your Mind’ – they were basically the same lyric that was written from two different standpoints,” Carter Cash told DJ Zane Lowe. Johnny “wrote ‘You Never Knew My Mind’ in 1967. I assume and I’m fairly certain it was written for his first wife, Vivian. That was the year that their divorce was legal. It was also the year where his love for my mother flourished. … And Chris took the two pieces and put them together in this one … I can’t listen to it without it laying me down. I mean it still, and it did that before Chris passed.”

In addition to being a post-mortem on Cash's first marriage, “You Never Knew My Mind” also reverberates in regard to Cornell’s suicide at age 52, which caught even those closest to the singer by surprise. On the song’s final verse, Cornell sings, “Sometimes I'm a stranger to you / Sometimes you're a stranger to me / Sometimes, maybe all the time / You never really knew my mind / I never really knew your mind.”

“Death Letter,” Johnny Winter

Not only can fans hear Johnny Winter’s final studio recording, they can also see it happen. His acoustic, gut-bucket rendition of Son House’s famous “Death Letter” was filmed and later released as a video.

It’s not likely that anyone knew that the recording would be Winter’s last, especially because it was made on Feb. 4, 2013, more than a year before his death at age 70 on July 16, 2014, while on tour in Europe. And it just happened that Winter’s final turn in the studio would be a song revolving around death – although the lyrics are not about the singer’s, but his lover’s, passing.

“Watching him do this performance of the Son House classic ‘Death Letter,’ you can hear how natural and comfortable it was for him,” Warren Haynes told Rolling Stone. “He’d been listening to and covering Son House his whole life, which comes across here but somehow sounds equally like Johnny Winter.”

“Death Letter” was released posthumously on Winter’s final studio album, Step Back, in September 2014. It is one of only two tracks that feature no special guests: Eric Clapton, Leslie West, Billy Gibbons and Joe Perry appear elsewhere. But for his last recording, Winter got to go out alone. In the video of the solo session, his last words are, “I’m ready to go home.”

“One Too Many Mornings,” the Band

Considering that the Band’s history is inseparable from Bob Dylan’s career, it’s fitting that the group covered a Dylan song on their final recording. “One Too Many Mornings” was recorded in 1999, the same year that Rick Danko died at the age of 56. The Band broke up, permanently, soon after.

Of course, some thought that the Band was finished after their 1976 Thanksgiving concert in San Francisco, the show filmed for Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz. But that performance, marvelous though it was, merely signaled Robbie Robertson’s last dance with the Band; the other four members (Danko, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson) got back together in 1983.

The reunion soldiered on despite Manuel’s 1986 suicide (he was 42), with three-fifths of the original group continuing to record and tour with new members Jim Weider, Randy Ciarlante and Richard Bell. The Band released three studio albums in the ’90s, two of which featured a Dylan song.

So, when the House of Blues was organizing another one of its tribute discs to classic artists (two compilations, covering songs by the Rolling Stones and Janis Joplin, were already complete), it was natural that the company would tap the Band for a Dylan-focused album. “One Too Many Mornings” was an interesting choice for a cover, not only because the Band (back when they were called the Hawks) backed Bob’s electric revision of his song at every date on his 1966 tour, but also because a recording of their anthemic version had been released in 1998 as part of Dylan’s “Bootleg Series.”

Yet there are a million miles between the ’66 live version (which doesn’t feature Helm, as he had yielded his drum stool to Mickey Jones) and the ’99 recording, spotlighting Danko and his sour-honey lead vocals, Helm on drums and harmonica and Hudson’s carnival of a Hammond organ. In addition, Derek Trucks played slide guitar on the track.

When Tangled Up in Blues (as the tribute album was titled) arrived in July 1999, the Band’s lived-in, strong take on “One Too Many Mornings” closed the compilation. By year’s end, Danko was gone and the Band were no more, for certain this time.

“Ride On,” Bon Scott (with Trust)

Bon Scott participated in an early session for Back in Black, the AC/DC album that ended up being dedicated to his memory. But he merely joined bandmates Angus and Malcolm Young as they figured out “Have a Drink on Me” and “Let Me Put My Love Into You,” accompanying the brothers on drums rather than singing.

Around the same time, in mid-February 1980, Scott sang on his last studio recording with another band, the French group Trust. He had gone over to London’s Scorpio Sound Studio with fellow Australian rocker Mick Cocks to party with the French metal band.

“We met a year earlier in Pathé studios in Boulogne through a friend of Keith Richards,” Trust singer Bernie Bonvoisin told Paris Match in 2015. “A friendly and musical love at first sight: He propose[d] me to open for AC/DC in a series of memorable concerts in France.”

Trust were recording their second studio album Repression at the time, but were happy to host Scott, who was riding high on the success of 1979’s Highway to Hell. Bonvoisin recalled Scott downing a bottle of whiskey while “helping” with the English language liner notes for the Trust’s forthcoming release. Soon, the boys began an impromptu jam of “Ride On,” an AC/DC tune that Trust had included on their debut album. Scott joined in to help sing the slow, bluesy song, which included the line “I ain’t too old to die.”

Within six days, between the night of Feb. 18 and the morning of Feb. 19, Scott passed out and died at the age of 33. This, like Brian Jones’s death, was ruled “death by misadventure.” Scott’s bandmates in AC/DC and his pals in Trust were shocked by the news. The studio jam version of “Ride On,” because of its status as Bon’s last recording, later surfaced on bootlegs.

“Salon and Saloon,” Jim Croce

Jim Croce’s last recording was made as a gift to his friend, creative partner and lead guitarist Maury Muehleisen. As such, it was a song that Muehleisen, not Croce, had written.

Before Croce earned fame in the early ’70s, his and Muehleisen’s roles were reversed. Maury was the one with the record contract and Jim assisted him on rhythm guitar. But once the two started working on Croce’s songs, with Muehleisen helping him out on the guitar arrangements, Maury essentially became Croce's lead guitarist. Croce was grateful for his friend’s generosity and showed his gratitude by recording one of Muehleisen’s songs, “Salon and Saloon,” for his third LP.

Muehleisen was inspired to write “Salon and Saloon” around the time that he and Croce first began playing together in 1970. The song is based in truth, an afternoon of two old high school pals catching up on where their lives had taken them since graduation. Muehleisen attended St. Mary’s Cathedral High School in Trenton, N.J., and was friendly with Mary Mitchell. The two of them earned reputations for being dedicated to their passions; his was music, hers was ballet. They happened to see each other by chance at the Trenton train station and hung out for the rest of the day.

“We talked about how our classmates had changed, and speculated on how they must have thought we’d changed,” Mitchell later recalled. “I was going to school in New York and worked as a fashion model to earn spending money. Maury looked very much the creative, long-haired artist that he was. It never occurred to me that we must have looked pretty odd together that day.”

Muehleisen channeled his good feeling into a song, naming it “Salon and Saloon,” because model Mary looked like she had walked out of the former, while he looked like he had stepped out from the latter. Maury might have been planning to record the song himself – he was hoping to get back to making his own records after Croce’s 1973 fall tour – but was delighted when Croce decided to cover the tune.

“Jim really loved the song and wanted to record it as a gift to Maury,” Maury’s sister Mary told Guitar World in 2013. “Jim sang and Tommy West played the piano. There are no guitars on the recording. It was the last song Jim ever recorded.”

Croce’s version of “Salon and Saloon” completed an album that would be released as I Got a Name. The sessions, which took place at New York’s Hit Factory, ended on Sept. 14, 1973. In less than a week, on Sept. 20, both Croce and Muehleisen would be gone.

While on tour in Louisiana, the two musicians – along with comedian George Stevens, manager and booking agent Kenneth D. Cortese, road manager Dennis Rast and pilot Robert N. Elliott – died when Elliott clipped a pecan tree upon takeoff from Natchitoches Regional Airport and crashed the twin-engine plane. Croce was 30. Muehleisen was 24. Their friends and family were stunned.

I Got a Name, with “Salon and Saloon” as the second song on side two, was released a few months later, on Dec. 1. The 1973 LP proved to be another big hit, leaving fans wondering what Croce and Muehleisen might have been able to achieve had they not gotten on that plane.

“Electra,” Dio

Although the Black Sabbath offshoot band Heaven & Hell dominated Ronnie James Dio’s musical career in his final years, both in terms of touring and recording, he was planning his eponymous band’s next project before he became gravely ill in the fall of 2009.

Back in 2000, the Dio band released Magica, a concept record about a battle between forces of good and evil set in a netherworld called Blessing. The plan from the start was that Magica would be the first part of a trilogy of albums that the group would eventually record. Ronnie’s Heaven & Hell commitments from 2007-09 delayed writing songs for the next two installments, although he revealed that he had “seven or eight” tracks started in an October 2009 interview.

Around that time, Ronnie even began moving past the demo stage, requesting guitarist Doug Aldrich’s assistance on a track, which has never been released. “We were kind of bouncing around some of his ideas and working on some of them,” Aldrich told Roppongi Rocks in 2017.

“Before we did ‘Electra,’ he had this other one that he said, ‘Can you put a solo on this?’ and he gave me the track," Aldrich added. "I had put a solo on it and then, when I brought it to his house, he goes, ‘No, no, no. I’ve got this new idea called ‘Electra." We didn’t even listen to it. I don’t even think he ever heard the solo because we were so focused on trying to get one song done to promote the tour that we were gonna do.”

After years of little activity for Dio, Ronnie’s plan was to revive the band with a tour, release a single from the forthcoming Magica II and III as a teaser, then record those albums in 2010. “Electra” became that teaser single, featuring Ronnie on vocals, Aldrich on guitar, Rudy Sarzo on bass, Simon Wright on drums and Scott Warren on keyboards. The fantastical track includes the lyric, “And it’s the last thing you’ll do,” which turned out to be tragically prophetic.

Not long after completing the recording of “Electra,” Dio was diagnosed with stomach cancer in November 2009. All touring and recording was called off while Dio sought treatment for the disease. In February 2010, “Electra” was given a special release as part of the Tournado box set that would have been available to fans on Dio’s tour, before it was cancelled.

Sadly, Ronnie’s stomach cancer metastasized and he died from the disease on May 16, 2010. The man who made “metal horns” famous was gone at the age of 67. “Electra” is the last song that Dio recorded – and released, at least so far – and is the only song from the Magica sequels that has been put out officially. After Ronnie’s death, it appeared on a compilation, as well as a bonus track on the deluxe re-release of the original Magica album.

“Louder Than Words,” Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd’s final recorded song was the result of a creative process that spanned more than 20 years. That’s because the tune, like much of the instrumental material on Floyd’s final album The Endless River, was rooted in the 1993 sessions for The Division Bell. Although Rick Wright had died in the following years, his bandmates David Gilmour and Nick Mason were able to tweak, merge and enhance the ideas, melodies and sounds from those days – aided by co-producers Phil Manzanera, Andy Jackson and Martin “Youth” Glover.

Unlike the rest of the vast majority of 2014’s The Endless River, “Louder Than Words” is less a component of a pseudo-ambient piece and more of a proper song, featuring the only lyrics on the album – sung by Gilmour and written by his wife Polly Samson. Having already worked on lyrical ideas for The Division Bell, Samson brought an idea to her husband’s attention during this project. It had been inspired by watching Pink Floyd’s famous reunion at 2005’s Live 8.

“At Live 8, they’d rehearsed, there were sound checks, lots of downtime sitting in rooms with David, Rick, Nick, and, on that occasion, Roger [Waters],” she recalled to Entertainment Weekly. “And what struck me was, they never spoke. They don’t do small talk, they don’t do big talk. It’s not hostile, they just don’t speak. And then they step onto a stage and musically that communication is extraordinary.”

She wrote a piece that focused on the band members’ musical connection, despite Pink Floyd’s more-than-occasional struggles with group harmony off the stage. When Samson presented Gilmour with the words, he thought it was a great capstone to the band’s career and matched with music that he had already been working on. The finished track had one foot in 1993, by featuring Wright’s keyboard playing, and one in 2014, with Gilmour’s newly recorded vocal at his home studio. Glover said that the Pink Floyd singer-guitarist waited until the end of the new sessions to lay down his vocal.

“Both Phil and myself had been pushing David to get the lyric and get the vocal,” Glover told Uncut. "Everyone around him was saying how he hates doing vocals, and he always leaves them to the last minute. ... He does this amazing thing when he's composing and gets a melody. He does this skat vocal. It is absolutely perfect. Apparently that's how he did ‘Comfortably Numb.’ I’ve never heard a singer skat a lead vocal so exact, with the right emotion and everything.”

Once Samson had the lyrics, the entire song came together as a meditation on how what bound together the guys in Pink Floyd was stronger than what got in the way. Although Gilmour, Mason and Waters (who left the group in the ’80s) are still alive and active in the music industry, they’ve given scant hope that there is any more Pink Floyd music in the future.

“Anything of value is on The Endless River,” Gilmour told Rolling Stone. “Trying to do it again would mean using second best stuff. That’s not good enough for me.”